October is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Awareness Month, and its mission is to improve the public's understanding of ADHD by providing reliable information based on scientific research. This year’s theme is about reframing ADHD, breaking misconceptions and stereotypes, and discovering new perspectives.

Redefining ADHD

ADHD is one of the most common childhood-onset neuropsychiatric disorders characterized by clinically significant inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity. Yet despite the self-descriptive nomenclature, ADHD is not uniquely a disorder marked by attention or hyperactivity but also involves cognitive abilities and executive behaviors. The three primary subtypes can be recognized by: 1) predominantly inattentive, 2) hyperactive-impulsive, and 3) combined, which may even be distinct disorders.

ADHD is not a simple disorder but is heterogeneous in neuropsychology, neurobiology, and comorbidities with other neurodevelopmental disorders. There are some people with ADHD who have never been hyperactive, but sometimes struggle with cycles of inattention or hyperfocusing. Consequently, it is essential for parents, schools, and teachers to identify such behavior and encourage the development of important strengths that they may have such as creativity, energy, enthusiasm, and problem-solving abilities.

According to the diagnostic classification systems ICD-10 and DSM-V (1, 2), one of the ADHD main symptoms is: “the child often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes“. However, the hyperfocusing state is often described as a positive experience because it engages them to perform tasks for more extended periods than neurotypicals. The DSM-V does not explicitly mention hyperfocusing as a symptom, but clinical psychologists describe it as intensive concentration on non-routine and stimulating activities accompanied by an isolation from everything else around (3).

Epidemiology and Etiology of ADHD

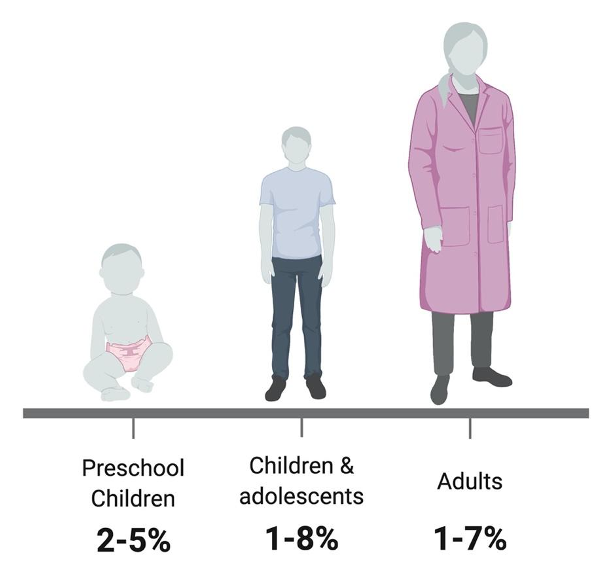

Precise data on the prevalence of ADHD is currently lacking. Meta-analysis on approximately 200 research studies worldwide estimated an ADHD prevalence at >7% (4). Moreover, it is crucial to note that ADHD does not only affect children. Symptoms often persist into adulthood, being reduced by around two-thirds relative to childhood (5). Additionally, ADHD symptoms often change throughout development. Hyperactivity may be replaced by akathisia (motor restlessness or constant urge to move) and insomnia. Inattention may manifest as difficulty completing work-based activities and forgetfulness.

As with most neurodevelopmental disorders, the spectrum of ADHD has been shown to be caused by atypical brain development due to genetic and environmental factors. Twin and family studies have further shown substantial genetic contribution to the disorder, with heritability ranging from 60-90% (6). Unfortunately, the mechanism of action is not entirely understood. Moreover, environmental factors such as prenatal and postnatal components may play an important role in the pathogenesis of ADHD.

While technological advances are moving at a rapid pace, unraveling the genetics of ADHD will be challenging. The next decade of work using technological advances and artificial intelligence (AI) should provide us with more accurate measures of brain structure and function alongside high-throughput and comprehensive ‘Omics’ data. These advances will set the stage for breakthroughs in our understanding of the etiology of ADHD and in our ability to diagnose and treat the disorder.

Figure 1: ADHD prevalence rates in different age groups (7, 8).

ADHD neurobiology

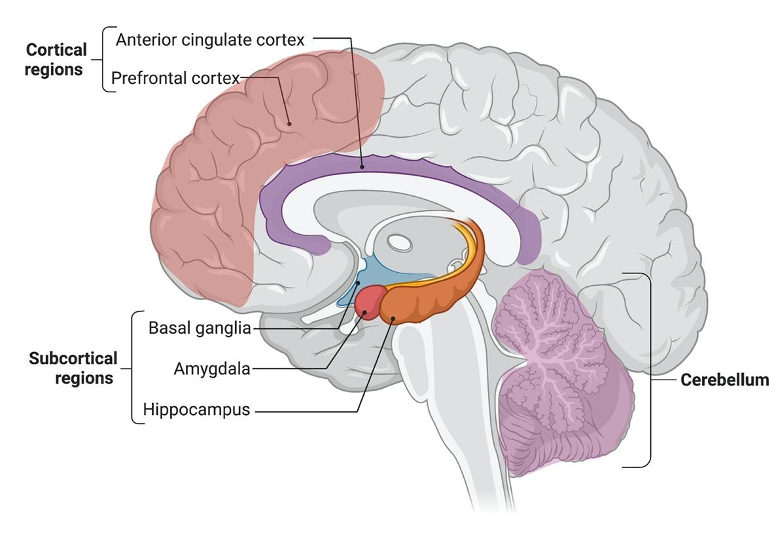

The neurobiology of ADHD is complex and involves multiple pathways, as well as structural and morphological alterations of the brain. Imaging studies, reporting alterations in brain structure and functional networks, suggest that ADHD affects both cortical dysfunction and atypical connectivity. The three areas of the brain commonly implicated in ADHD include 1) cortical regions (prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex), 2) subcortical regions (limbic system including amygdala and hippocampus, and basal ganglia), and 3) the cerebellum (Figure 2) (9, 10). Consequently, it has been noted that the brain volume of individuals with ADHD seems to be smaller in subcortical areas (responsible for attention) and the limbic system (emotional processing and impulsivity) as well as the overall brain size. These differences were more significant in children, but relatively minor in adults (9).

Figure 2: The three areas of the brain implicated in ADHD.

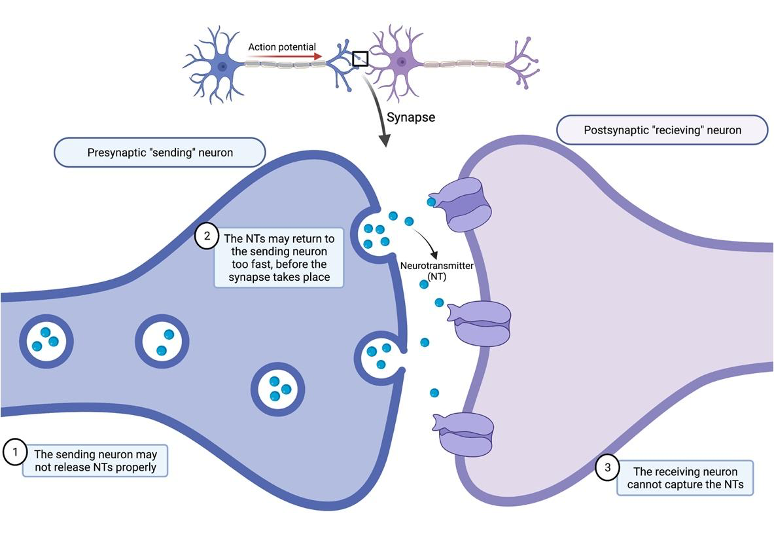

Others have highlighted the importance of a dysregulation of the dopamine and norepinephrine neurotransmitters, their consequent effect on multiple neural pathways and thus likely contributors to ADHD (11). An interesting area of research would be to investigate the regulation of presynaptic neurotransmitter release as well as post synaptic neuronal intake of dopamine and norepinephrine as a driver of ADHD development and variability (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Synaptic dysregulation in ADHD brain.

Comorbid psychiatric disorders associated with ADHD

Comorbidity between neurodevelopmental disorders is common. While we need to be aware of co-occurring conditions, we also need to focus on individual strengths. Most individuals with ADHD have a diagnosed or undiagnosed psychiatric comorbidity. Early comorbidities concurrent with ADHD may include autism spectrum disorder (ASD), tic disorder, anxiety, major depression, and intellectual disability. While many of these disorders are complexly intertwined, it would be valuable to have the ability to objectively distinguish between the different groups. Not only would this contribute to a deeper understanding of these disorders, but further contribute towards more personalized treatment methodologies. One of the goals of QBRI’s Neurological Disorders Research Center is to advance biomarker discovery in the field of neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as combine ‘Omic’ studies, and integrative AI approaches, to develop a clearer understanding of disorders such as ADHD.

Contributed by: Dr. Salam Salloum-Asfar (Postdoctoral Researcher, QBRI) & Dr. Sara A. Abdulla (Research Fellow, QBRI)

Arabic translation and text validation: Rowaida Z. Taha (Research Associate, QBRI)

Editors: Dr. Adviti Naik (Postdoctoral Researcher, QBRI), Dr. Prasanna Kolatkar (Senior Scientist, QBRI)

For references, please click here.

Related News